Polyamides, commonly referred to simply as nylon, remain one of the most versatile and widely used engineering thermoplastics because they deliver a rare combination of strength, toughness, wear performance, and chemical resistance, while remaining highly modifiable through reinforcement and compounding. Their performance is not “one-size-fits-all,” however. Nylons exist in many forms—aliphatic, semi-aromatic, and aromatic—and the details of the molecular structure, especially the ratio of carbon atoms to amide groups, strongly influence mechanical properties, thermal capability, moisture uptake, and long-term durability.

This paper provides a practical framework for understanding nylon performance and selecting among common nylon families. It begins with the nylon functional group and polymerization routes, then summarizes characteristic mechanical and thermal behavior, followed by the critical relationship between nylons and water. Finally, it addresses environmental degradation mechanisms—including hydrolysis, thermal oxidation, photodegradation, and chemical attack—and concludes with a concise guide to key nylon types and where they are most appropriately applied.

What is a Polyamide?

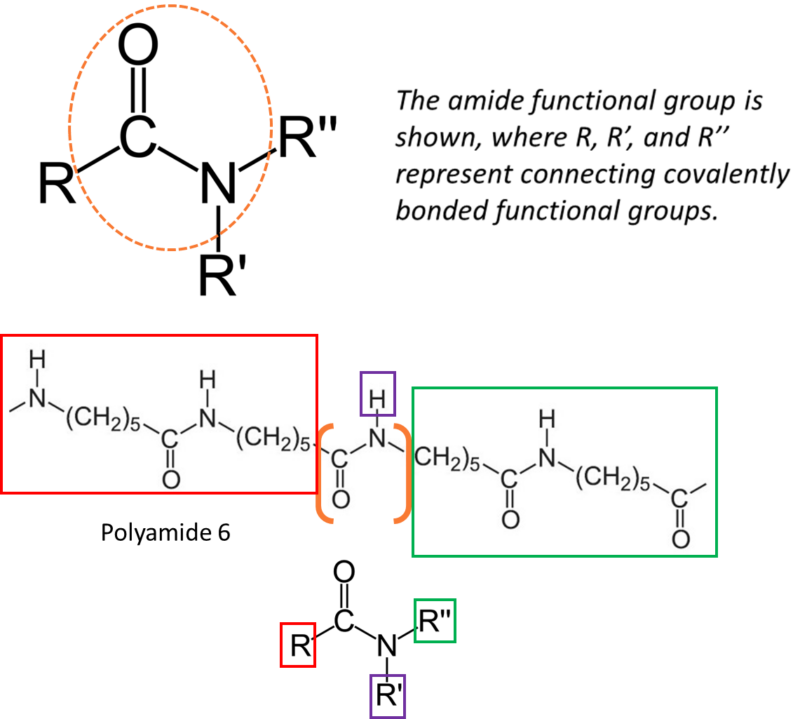

The amide function group is illustrated by nylon 6.

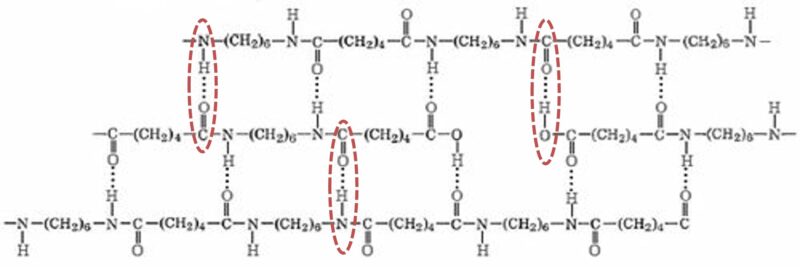

A polyamide is a macromolecule with repeating units linked by amide bonds. The amide functional group features a nitrogen atom attached to a carbonyl carbon. This chemistry is central to nylon performance because amide groups support strong intermolecular interactions, particularly hydrogen bonding, which contribute to strength, stiffness, and thermal capability.

Nylons are commercially available in many grades and families. Their versatility makes them among the most widely used engineering thermoplastics, and the structure, especially the ratio of carbon atoms, drives differences among nylon types.

Semi-Crystalline Structure: Why It Matters

Most common nylon resins are semi-crystalline, meaning they contain both amorphous and crystalline regions. This morphology produces two key thermal transitions: a glass transition temperature (Tg) and a melting temperature (Tm). There is no such thing as a 100% crystalline polymer, and the balance between crystalline and amorphous regions is a major reason nylons can provide both high strength, impact resistance, and practical processability.

In practice, semi-crystalline polymers tend to exhibit a distinct melting point and are commonly opaque or translucent. They often show good organic chemical resistance, high tensile strength and modulus, superior fatigue resistance, better creep resistance, and higher mold shrinkage relative to amorphous materials.

Chemistry and Polymerization: Understanding the Naming

Polyamides compounds occur naturally as proteins like wool and silk. They are also produced synthetically. Synthetic nylons are commonly categorized as aliphatic, semi-aromatic, or aromatic.

Aliphatic Nylons: Lactams – Single Monomer Route

Common aliphatic “single number” nylons (e.g., PA 6, PA 11, PA 12) can be produced by polymerization of a lactam ring, where the monomer contains both amine and acid functionality. The nylon type corresponds to the number of carbon atoms in the lactam monomer.

The structure of nylon 11 is shown.

Aliphatic Nylons: Dual Monomers – Condensation Route

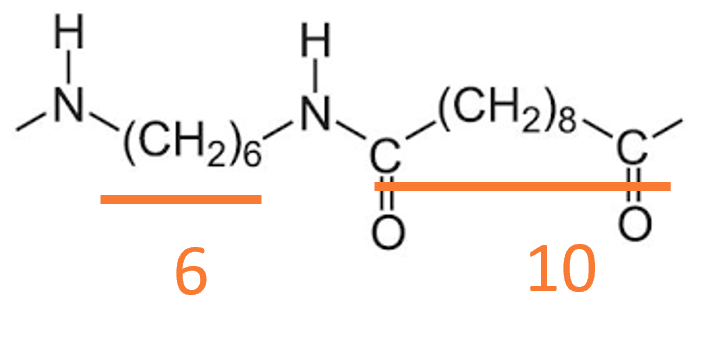

“Dual number” nylons (e.g., PA 6/6, PA 6/10, PA 4/6) are produced through a condensation reaction between diamines and dibasic acids, creating a nylon salt and then polymerizing. The first number refers to the carbon atoms in the diamine; the second refers to the carbon atoms in the acid component.

The structure of nylon 6/10 is shown.

Semi-Aromatic Nylons

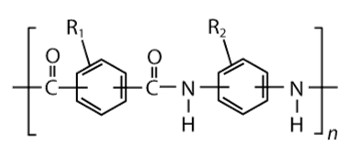

Semi-aromatic nylons are commonly referred to as polyphthalamides (PPA). They are formed by condensation between aliphatic diamines and aromatic diacids, notably terephthalic acid and isophthalic acid.

The structures of typical PPA resins are shown.

Aromatic Nylons

Aromatic nylons are commonly referred to as polyarylamides (PARA). Their polymerization commonly involves condensation of an aromatic diacid halide with an aromatic diamine.

The basic structure of PARA is shown.

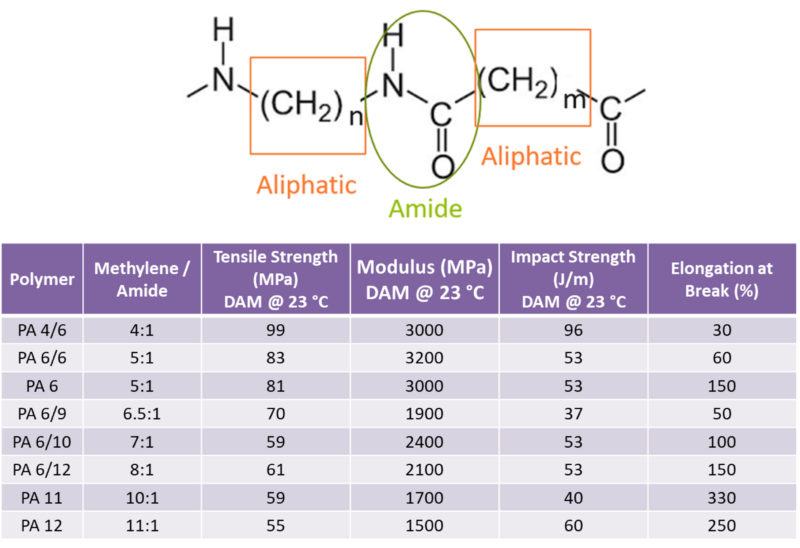

Unfilled aliphatic nylon resins tend to show broadly similar stress-strain behavior, and it is common for tensile strength at break to be higher than tensile stress at yield due to substantial plastic deformation. A useful practical trend is that tensile strength at break and yield generally decrease as amide concentration decreases; in other words, as hydrocarbon content increases, strength tends to decline. This connects back to the role of intermolecular forces and hydrogen bonding: applied stresses must overcome those forces, and higher amide content generally means more hydrogen bonding. Modulus also generally decreases as amide concentration decreases; higher hydrocarbon content typically increases flexibility. Ductility trends can be less straightforward; impact strength and elongation at break do not always correlate cleanly with amide concentration.

Nylon Performance: Mechanical and Thermal Behavior

Unfilled aliphatic nylon resins tend to show broadly similar stress-strain behavior, and it is common for tensile strength at break to be higher than tensile stress at yield due to substantial plastic deformation. A useful practical trend is that tensile strength at break and yield generally decrease as amide concentration decreases; in other words, as hydrocarbon content increases, strength tends to decline. This connects back to the role of intermolecular forces and hydrogen bonding: applied stresses must overcome those forces, and higher amide content generally means more hydrogen bonding. Modulus also generally decreases as amide concentration decreases; higher hydrocarbon content typically increases flexibility. Ductility trends can be less straightforward; impact strength and elongation at break do not always correlate cleanly with amide concentration.

The mechanical properties of nylon resins correlate to the relative amounts of amide and aliphatic methylene content.

For semi-crystalline nylons, the relationship to Tg and Tm is central. Below Tg, they can be stiff and sometimes brittle. Above Tg, but below Tm, they behave as a soft, leathery solid without flowing. Above Tm, crystalline regions melt and the polymer can flow. The thermal transitions of nylons are determined by structure, and higher amide content generally results in higher thermal stability.

Nylon Performance with Water: The Most Misunderstood Variable

Nylons are hydrophilic and have an affinity for water, absorbing moisture from air and water. The practical consequence is that the properties of nylon parts are directly affected by their moisture content. Moisture acts as a plasticizer: it reduces strength and stiffness while increasing elongation and toughness, and it can shift the glass transition temperature.

Intermolecular hydrogen bonding within nylon produces many of its characteristic properties.

This behavior is tied to intermolecular bonding. Hydrogen bonding between polymer chains contributes to nylon’s mechanical and thermal properties. Like nylon, water also is subject to hydrogen bonding, and absorbed was interferes with nylon’s chain-to-chain bonding, allowing chains to slide more easily – effectively plasticizing the polymer. The effects of water absorption can be readily seen as decreased modulus and strength, and increased impact resistance in the short-term properties on nylon resins, However, it also negatively affects long-term performance, including creep resistance.

Moisture absorption depends on temperature and humidity, exposure time, part thickness, and nylon type. Importantly, as the number of aliphatic carbon atoms separating amide groups increases, moisture absorption generally decreases.

Environmental Effects: Degradation and Chemical Attack

Environmental factors can produce molecular degradation in nylons through mechanisms such as hydrolysis, oxidation, photolysis, and thermal exposure. In many applications, these mechanisms often overlap with stress and temperature, and the result is typically a loss in molecular weight and mechanical margin.

Hydrolysis is an important degradation mechanism for nylon resin, and it is important to understand that it is not the same as water absorption. Hydrolysis is degradation through contact with water, involving hydrogen cations (H⁺) or hydroxyl anions (OH⁻). Acids (high H⁺) and bases (high OH⁻) can dramatically accelerate the process. Hydrolysis reverses polymerization in condensation polymers, an important point when evaluating long-term exposure. It is explicitly different from simple water absorption.

A practical—and often underappreciated accelerating factor is the role of stress. Tensile stresses of only a few MPa can increase the rate of hydrolysis substantially, up to a factor of 10, through stress-enhanced diffusion, mechanically induced chain scission, and stress separation of chain ends that prevents recombination.

Nylons undergo thermal oxidation through free-radical formation, incorporating oxygen into the polymer backbone and creating carbonyl structural groups. The reaction rate increases with temperature and follows Arrhenius behavior, with oxygen in air as a key reactant.

Nylons are inherently susceptible to UV degradation through photooxidation. Aliphatic amide monomers may not absorb below 300 nm, but aliphatic nylons can absorb below 300 nm due to additives or low-level impurities, including polymerization by-products or oxidation products. Aromatic and semi-aromatic nylons contain chromophores inherent to their structure and are generally more susceptible to UV degradation than aliphatic nylons.

Nylons provide good resistance to many chemicals, but they can be attacked by strong organic and mineral acids, alcohols, alkalis, hot water, and metallic chlorides.

The engineering consequence of molecular degradation through hydrolysis, oxidation or photooxidation is familiar: loss of molecular weight which results in embrittlement, cracking, catastrophic failure risk; appearance changes including discoloration, loss of gloss, loss of transparency; volatiles evolution and odor generation; and the potential for the reduction of electrical resistivity.

Environmental Stress Cracking (ESC) is the premature embrittlement and cracking of a plastic due to the synergistic action of stress and contact with a chemical agent. For nylons, a key ESC category is exposure to aqueous solutions of metal halides, most commonly chloride and bromide salts, which can weaken intermolecular bonding and lead to local plasticization. Nylons with higher methylene-to-amide ratios show greater resistance to metal-halide stress cracking. Severity also varies by salt: zinc chloride is described as very severe, lithium/calcium/magnesium chlorides intermediate, and sodium chloride least aggressive among those listed. Higher temperatures reduce the threshold stresses required for cracking.

Figure 3 (placeholder): Metal halide ESC severity ranking (insert slide image).

Selection Guide: Common Nylon Families and Best-Fit Applications

Below is a practical summary of key nylon types. The intent is not to replace datasheets, but to anchor expectations and avoid predictable misapplications.

Nylon 6 (PA 6): PA 6 is often selected for good surface finish, strength, friction/wear performance, and hydrocarbon resistance, with the usual cautions about water absorption and poor resistance to strong acids and bases. Relative to PA 6/6, it often offers improved appearance and processability, but has lower modulus and absorbs moisture more rapidly.

Typical applications include industrial machinery, material handling equipment, transportation, appliances, and electrical/electronic devices.

Nylon 6/6 (PA 6/6): PA 6/6 is a strength/stiffness/workhorse with improved heat resistance, wear resistance, and lubricity, balanced against high water absorption and sensitivity to strong acids/bases. It has a higher melting point than PA 6 and is positioned for superior elevated-temperature performance and improved creep resistance.

Low-Moisture Aliphatic Nylons, PA 6/12 and PA 6/10: PA 6/12 was developed as a low-moisture absorbing nylon, reducing swelling relative to PA 6 and PA 6/6, though the reduced moisture uptake also corresponds to reduced ductility versus those families. PA 6/10 likewise offers lower moisture absorption, good chemical resistance, and room-temperature toughness at low temperatures, and better resistance to salt-driven stress cracking such as zinc chloride.

Nylon 4/6 (PA 4/6): PA 4/6 is positioned for elevated-temperature strength and stiffness, hydrocarbon resistance, and metal replacement opportunities, with limitations including high water absorption, dimensional change with water uptake, and darkening with high heat exposure.

Bio-Based / Specialty Aliphatic Nylons, PA 11 and PA 12: PA 11 is noted as a bio-based nylon derived from castor oil, with strong impact properties and good chemical resistance relative to other nylons, balanced against lower strength/stiffness and minimal heat resistance.

PA 12 is similarly low-moisture absorbing with good chemical and electrical properties; transparent grades are available.

Semi-Aromatic High-Performance Nylon Polyphthalamide (PPA): PPA is typically selected for higher thermal capability, chemical resistance, lower moisture sensitivity relative to aliphatic nylons, and strong creep and fatigue resistance, while requiring disciplined drying and often higher processing temperatures.

Aromatic High Strength Nylon Polyarylamide (PARA): PARA provides high temperature resistance, chemical resistance, creep resistance, and comparatively low moisture absorption. It often contains high glass fiber loadings (50–60%), delivering very high strength and stiffness while maintaining a smooth, resin-rich surface finish.

Amorphous Nylons: It is also possible to produce amorphous nylons, not semi-crystalline, offering transparency, low shrinkage, dimensional stability, and good chemical resistance relative to other amorphous resins.

In addition, many nylon blends and alloys exist as cost-effective methods to tailor chemical resistance, impact performance, weathering, and high/low temperature behavior.

Conclusions

Nylons earn their place in engineering applications because they provide strong baseline performance, and because they can be engineered further through reinforcement, compounding, and family selection. The practical selection challenge is that the same chemistry that makes nylons strong (amide functionality and intermolecular bonding) also makes them sensitive to moisture and, in specific environments, to degradation mechanisms such as hydrolysis and metal-halide-driven ESC.

When nylon performance disappoints, the root cause is often not “nylon is bad,” but that the wrong nylon family was selected, moisture conditioning was not accounted for, the environment includes a known stress-crack agent, or the part is operating in a regime where long-term durability mechanisms dominate. The good news is that these risks are manageable—if they are identified early, and if validation testing reflects real service conditions. If you are working through nylon selection, unexpected cracking, durability concerns, or environmental compatibility questions, The Madison Group can help with material selection support, failure analysis, and validation testing strategy.