One of the most common analytical techniques for exploring the composition of plastic materials is Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. Spectroscopy is the study of how light interacts with matter. FTIR is a non-destructive, non-consuming analytical technique that provides insight into the molecular structure and functional groups of organic, and some inorganic, compounds by studying their molecular vibrations.

Several keys to successfully using this technique include the sampling method, sample preparation, and interpretation of the infrared spectrum. This article will review basic concepts of FTIR that may help you successfully create and understand an FTIR spectrum when analyzing the composition of a plastic component.

Fundamentals and Theory of FTIR Spectroscopy

The FTIR Spectrum

When showing the results in absorbance mode, the y-axis displays how much infrared light has been absorbed by the sample at each wavelength (or wavenumber). Absorbance is a measure of how strongly the sample interacts with light at specific frequencies, which correspond to various molecular vibrations. The spectrum can also be presented in transmission mode, which is essentially the inverse of the absorbance mode. The x-axis is commonly plotted as the wavenumber, which is the reciprocal of the wavelength. The wavenumber relates to frequency by the equation:

Wavenumber [cm-1] = frequency [sec-1] / speed of light [cm/sec]

Peaks on the absorbance spectrum indicate where specific molecular bonds absorb IR light and vibrate, providing a “fingerprint” of the molecule’s structure.

Molecular Vibrations and Hooke’s Law

When an organic compound is exposed to infrared light, its molecules absorb specific portions of the light energy, causing the bonds to stretch and undergo other types of vibrations. The stretching of a bond is comparable to the behavior of a spring, as illustrated in Figure 1, where k represents the spring stiffness constant and m denotes the mass.

Figure 1 – Representation of a chemical bond with a spring – mass system.

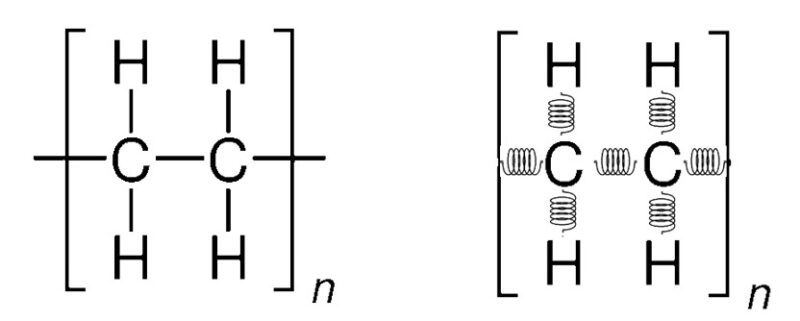

A molecule, consisting of numerous bonds, can be modeled as a system of springs representing each bond, Figure 2. This results in a distinctive array of absorbances, creating a unique spectrum for each molecule.

Figure 2 – Molecular structure for polyethylene. Bonds of polyethylene represented with springs.

For molecular stretching, a bond can be modeled as two masses connected by a spring and follows Hooke’s Law. The frequency of the stretching oscillation for this spring-mass system can be determined using the following equation:

frequency= 1/2π √(k/μ)

Where k is spring constant, or the bond strength, which is approximated as 5 x 105 dynes/cm for a single bond and roughly double this value for a double bond. μ is the reduced mass [m1m2/(m1 + m2)]. Where m1 and m2 are the atomic mass of the two atoms. By using appropriate mass units and expressing the equation in terms of the wavenumber, it can be reformulated as:

wavenumber= 4.12√(k/μ)

This equation allows for the estimation of the wavenumber associated with bond oscillations in stretching modes during IR energy absorption.

FTIR Spectroscopy Acquisition Techniques

The two primary spectral acquisition techniques are transmission and attenuated total reflectance (ATR).

Transmission FTIR

Transmission FTIR is the most traditional form of sample measurement, involving the IR beam passing entirely through the sample. The molecular or functional groups within the sample absorb the IR energy at specific frequencies (or wavenumbers). Sample preparation for Transmission FTIR can be more difficult and involved. The sample is commonly prepared to a specified thickness. Control of the sample thickness allows one to know the exact path length through which the IR light passes through the sample. This is critical for the application of Beer’s Law for calculating the absorption. Beer’s Law is given as:

Total absorption of the sample = Absorptivity x Length x Concentration

Absorptivity: amount of light absorbed at a particular wavenumber by a molecule.

Length: path length of the light beam or thickness of sample.

Concentration: the concentration of all molecules in the infrared beam through the sample.

As the Beer’s equation indicates, transmission IR can be used to provide insight into the concentration of a component within a simple sample. However, this technique is limited for multicomponent analysis when the sample involves numerous ingredients/additives. Most plastic parts are made of numerous additives that include the base resin, colorants, plasticizers, flame retardants, fillers, reinforcements, processing aids, mold release, multiple antioxidants, and other stabilizers. Unfortunately, these additives can absorb IR light at various similar and overlapping wavenumbers. It is rare for an additive to have a unique wavelength where another additive is also not absorbing. As described in the standard ASTM E 168, multiple calibration curves of known concentrations of each component of the sample must be created independently. This makes Transmission FTIR limited for analyzing the additive concentration of plastic materials that have more than several ingredients. A technique to consider for quantification includes chromatography and mass spectroscopy, which involves the separation of the plastic ingredients and then detection and quantification.

Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) FTIR

FTIR via ATR is the predominant method for acquiring a spectrum of a plastic sample, mainly due to its simplicity and minimal effort to prepare a sample and its ability to deliver high precision. FTIR-ATR involves passing infrared light through a crystal with a high refractive index, such as a diamond. The sample is placed in contact with the crystal, and the infrared light is directed into the crystal, where it reflects at the interface between the crystal and the sample. At each reflection, the light penetrates a short distance into the sample (1 – 4 micrometers), where it is absorbed, thus allowing the collection of the spectrum. The term “attenuated” refers to the reduction in intensity of the total internal reflection due to absorption by the sample. An understated benefit of this method is that, depending on the sample size and shape, it might not necessitate modifying the sample to obtain an FTIR spectrum.

Interpretation and Practical Application of FTIR Spectroscopy

Characteristic Bond Absorptions

The wavenumber equation allows for the approximation of the wavenumber range for common bond stretching modes. For example:

C – H bond: ~3000 cm-1

C = C bond: ~1700 cm-1

C ≡ C bond ~2100 cm-1

C – O bond: ~1100 cm-1

When bonds are exposed to light energy, they can exhibit various vibrational behaviors beyond stretching, such as scissoring, rocking, wagging, and twisting. These vibrational modes result in unique absorption patterns in the FTIR spectrum.

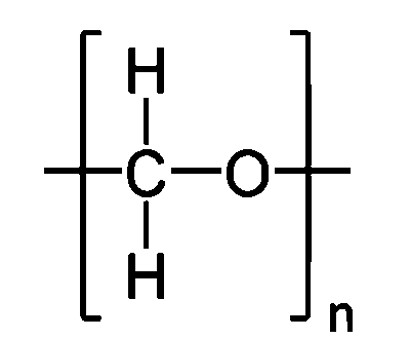

The monomer for polyoxymethylene (POM) (also known as polyacetal), containing carbon-oxygen and carbon-hydrogen bonds, is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Molecular structure representation for polyoxymethylene (polyacetal).

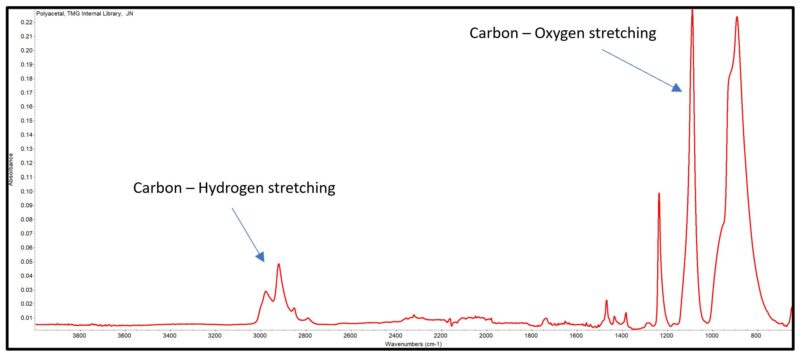

The FTIR-ATR spectrum for polyacetal is shown in Figure 4. The primary Carbon – Hydrogen and Carbon – Oxygen stretching absorption are pointed out. The other absorptions shown are related to the other vibration modes of the molecule, e.g., bending vibration absorption at 1468 cm-1.

Figure 4 – FTIR absorbance spectrum for polyoxymethylene (polyacetal).

Only vibrations that produce a change in the dipole moment at the bond will be observed on the infrared spectrum as signals. The intensity of the absorption is related to the strength of the dipole moment. As shown in Figure 4, the carbon – oxygen bond has a strong dipole moment, creating a strong signal in the infrared spectrum.

Challenges in Multicomponent Analysis

Plastic materials often contain a variety of ingredients in addition to the base polymer. While some additives exhibit distinctive absorptions, many have overlapping bands that can complicate spectral interpretation. In these cases, the expertise of the analyst becomes critical. Effective interpretation relies on experience using spectral subtraction and other spectral-manipulation techniques, as well as an understanding of where common additives absorb—skills developed through extensive practice.

Summary

FTIR spectroscopy is a powerful and widely used analytical tool for examining the composition of plastic materials, offering valuable insight into the molecular structure and functional groups present in a sample. The effectiveness of FTIR depends heavily on thoughtful sample preparation and a solid understanding of how infrared absorption relates to molecular vibrations, whether using transmission or ATR acquisition techniques. By recognizing how bond strength, reduced mass, and dipole-moment changes influence peak positions and intensities, the analyst can interpret the resulting spectrum as a molecular fingerprint. These foundational principles enable accurate identification of polymers and provide a basis for evaluating the chemistry of a plastic component. Although FTIR offers considerable compositional insight, its limitations, particularly in multicomponent materials, require experience and skill to navigate.

Learn more about Utilizing Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) for Plastics Failure Analysis .