Virtually validating plastic part designs through simulation has become an essential tool for engineers. It helps them develop high-quality new products while meeting today’s tight deadlines. Using structural finite element analysis (FEA) early in the design stage empowers engineers to make intelligent decisions about nominal wall thickness, stiffening rib placement, and material selection. What’s more, the integration of many structural FEA packages into traditional CAD software has made this powerful tool accessible to a much wider audience.

However, to truly unlock the potential of FEA for non-linearity in plastic part design, careful consideration of simulation inputs is crucial (remember: “Garbage In, Garbage Out”). A key decision designers face is whether to perform a non-linear analysis. While running a non-linear analysis can significantly boost simulation accuracy, it often requires considerably more computational time. So, when should an engineer opt for a non-linear analysis to ensure the integrity of their plastic designs?

Understanding Material Non-Linearity

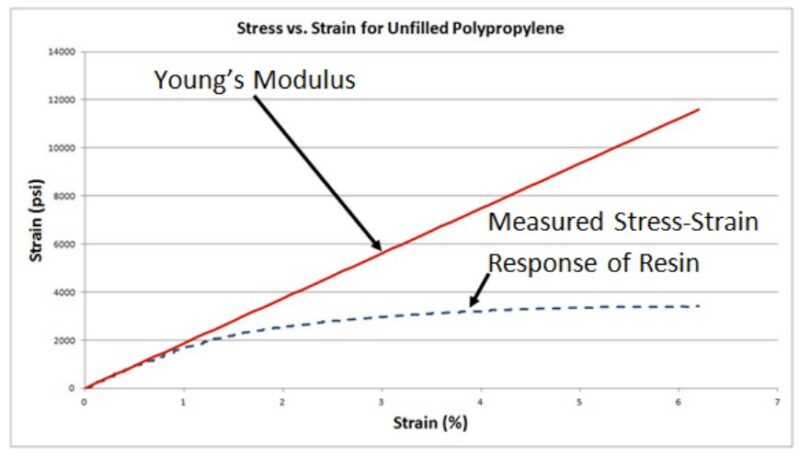

Most engineers and designers are taught that a material’s stiffness can be characterized by a single value: Young’s Modulus. This concept assumes a material’s response is directly proportional to the applied load. For example, if a cantilevered beam deflects 0.125 inches under a 10-pound load, it would deflect 0.250 inches if the load increased to 20 pounds. While Young’s Modulus simplifies material characterization, it also over-simplifies reality. In truth, all materials are inherently non-linear; it’s impossible to characterize a material with a single value for all load types and conditions.

Young’s Modulus becomes particularly problematic when characterizing polymers. Generally, polymers exhibit a very small linear region, with most resins deviating from this behavior at strains less than 1%. This highlights the importance of addressing non-linearity in plastic part design when analyzing material behavior.

Figure 1: Characterizing the stiffness of a plastic resin by using Young’s Modulus (i.e. linear assumption) can lead to an over-prediction in stress and stiffness of the part.

The point where material behavior deviates from linearity is known as the proportional limit. The danger of using Young’s Modulus beyond this limit is that the predicted stiffness and stress of the designed part will be overpredicted (Figure 1). Overpredicting these design parameters can lead to over-designing the part, minimizing the very benefits of using plastics in the first place. To avoid this material characterization oversight in non-linearity in plastic part design, designers and analysts should examine the polymer’s stress-strain behavior. This helps determine if Young’s Modulus accurately represents the material response over the strain range of interest. If not, a more accurate model should be used. Many refined models exist to better predict polymer behavior, and most commercial software allows users to import stress-strain data to account for this non-linearity in plastic part design.

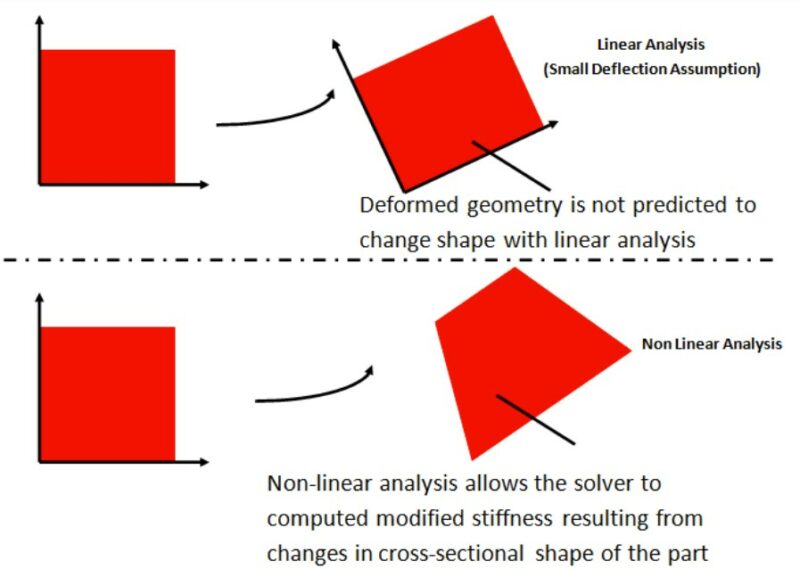

Figure 2: When parts experience large deflections and rotations, the cross-section of the geometry can change, which can alter the cross-section of the part. Only a nonlinear analysis can capture the geometry change of the part and resulting change in stiffness.

Accounting for Geometric Non-Linearity

Another source of non-linearity in plastic part design arises from changing geometric cross-sections due to loading. Geometric non-linearity considers that the geometry’s cross-section can change as a result of large deformations (i.e., large displacements, large rotations, or large strains). A linear analysis assumes a part’s stiffness remains constant regardless of deflection. If deflections are small relative to the part’s overall dimensions, assuming minimal geometric change is reasonable. However, as deflections increase, the resulting geometric change can lead to either a stiffer or more compliant structure (Figure 2).

It’s generally accepted that if the part’s rotation remains less than 10-15 degrees and deflection is significantly less than its overall dimensions, a linear analysis will yield reliable results. However, if an initial linear analysis shows large deformations and rotations, the analysis should be converted to non-linear to accurately account for the modified stiffness, directly addressing non-linearity in plastic part design.

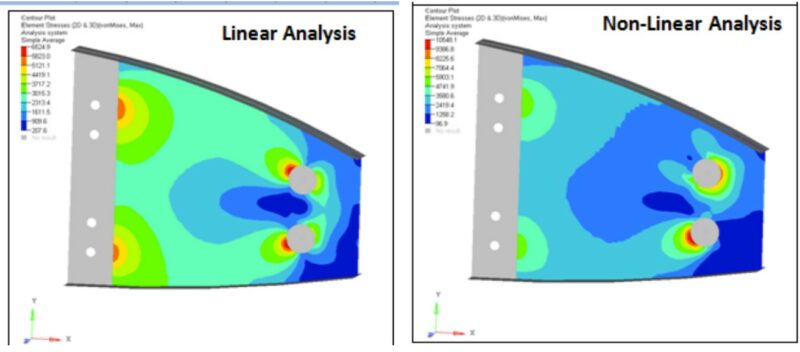

Addressing Boundary Non-Linearity (Contact)

Boundary non-linearity in plastic part design occurs when the boundary conditions in an FEA model change during the analysis. It’s particularly prevalent when modeling contact between mating components or during impact simulations. When modeling contact, the solver must constantly calculate and monitor the generated contact area under applied loads. This area is determined by how many nodes in each body are within a specified tolerance. If two nodes, on separate bodies, are within the prescribed tolerance, contact is considered closed, and a reaction force is applied to prevent further penetration. If the nodes remain outside the tolerance, contact is open, and no reaction force is applied. As the contact area between mating components changes, the force transfer between them also changes, altering the stress distribution at the interface. In a linear analysis, the solver assumes constant contact surfaces and doesn’t perform this crucial calculation.

Figure 3: Not accounting for the boundary non-linearity and changing contact areas during an analysis can lead to errant predictions in the stress distributions throughout the part.

Boundary non-linearity in plastic part design occurs when the boundary conditions in an FEA model change during the analysis. It’s particularly prevalent when modeling contact between mating components or during impact simulations. When modeling contact, the solver must constantly calculate and monitor the generated contact area under applied loads. This area is determined by how many nodes in each body are within a specified tolerance. If two nodes, on separate bodies, are within the prescribed tolerance, contact is considered closed, and a reaction force is applied to prevent further penetration. If the nodes remain outside the tolerance, contact is open, and no reaction force is applied. As the contact area between mating components changes, the force transfer between them also changes, altering the stress distribution at the interface. In a linear analysis, the solver assumes constant contact surfaces and doesn’t perform this crucial calculation.

Conclusion

Structural finite element analysis is a powerful tool that has expanded the possibilities for plastics across many fields. The ability to validate a plastic part design and make critical decisions about the final design can save significant time and money. However, care must be taken to ensure the analysis accurately models the physical system. Ensuring that the non-linear effects of the plastic material, loading conditions, and boundary conditions are accounted for in a simulation will help designers and engineers make correct decisions and bring their products to market faster, all while effectively managing non-linearity in plastic part design.